Information and Inflation

Published 24 January 2023

By Dr Peter J Phillips, Associate Professor (Finance & Banking) University of Southern Queensland

The “cost of living” is a trending topic in Australia, as it has been around the world since mid-2022. The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) increased interest rates dramatically to try to curb inflation. Unfortunately, months after the first rates increase, inflation was still much higher than the “target rate”. And that’s only “headline” inflation.

The official 7.3% inflation number recorded in late 2022 (the highest since the 1980s) is only part of the picture. Living expenses for many people might have risen by twice that, maybe more.

Big increases in living expenses are a problem, obviously, but inflation also messes up the information signals on which we base all kinds of decisions. A simple example is when you go to the supermarket with an array of prices in mind and a rough plan about what to buy only to find that something is suddenly a lot more expensive. Your intended purchasing decisions are disrupted by this new information and your “information system” (the knowledge of prices that you have gathered over time) is upset. It takes time to learn the new prices. There are more serious information distortions too, especially of the signals that are used by entrepreneurs to allocate capital to longer-term projects, like construction projects.

We got ourselves into this situation, in Australia and elsewhere, by printing too much money.

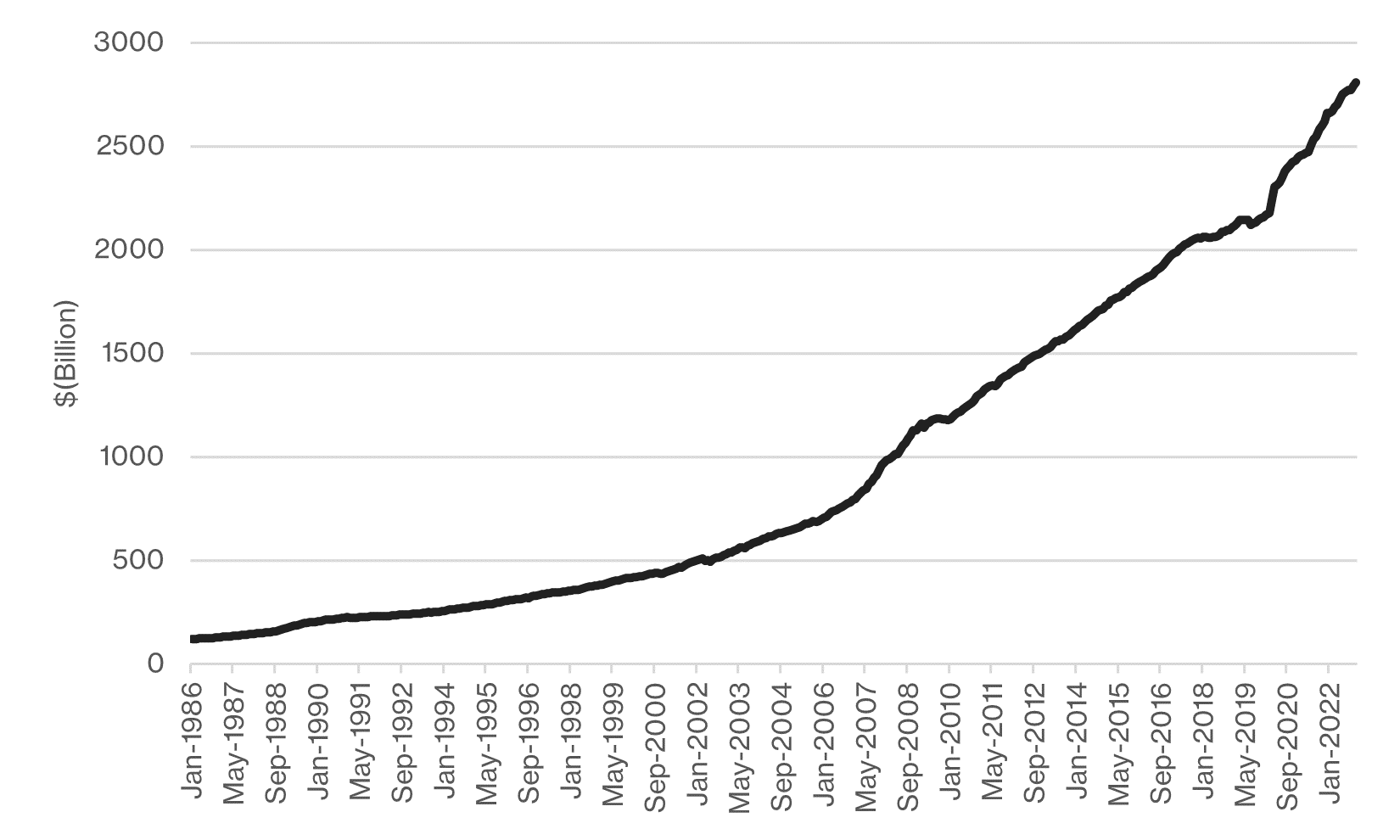

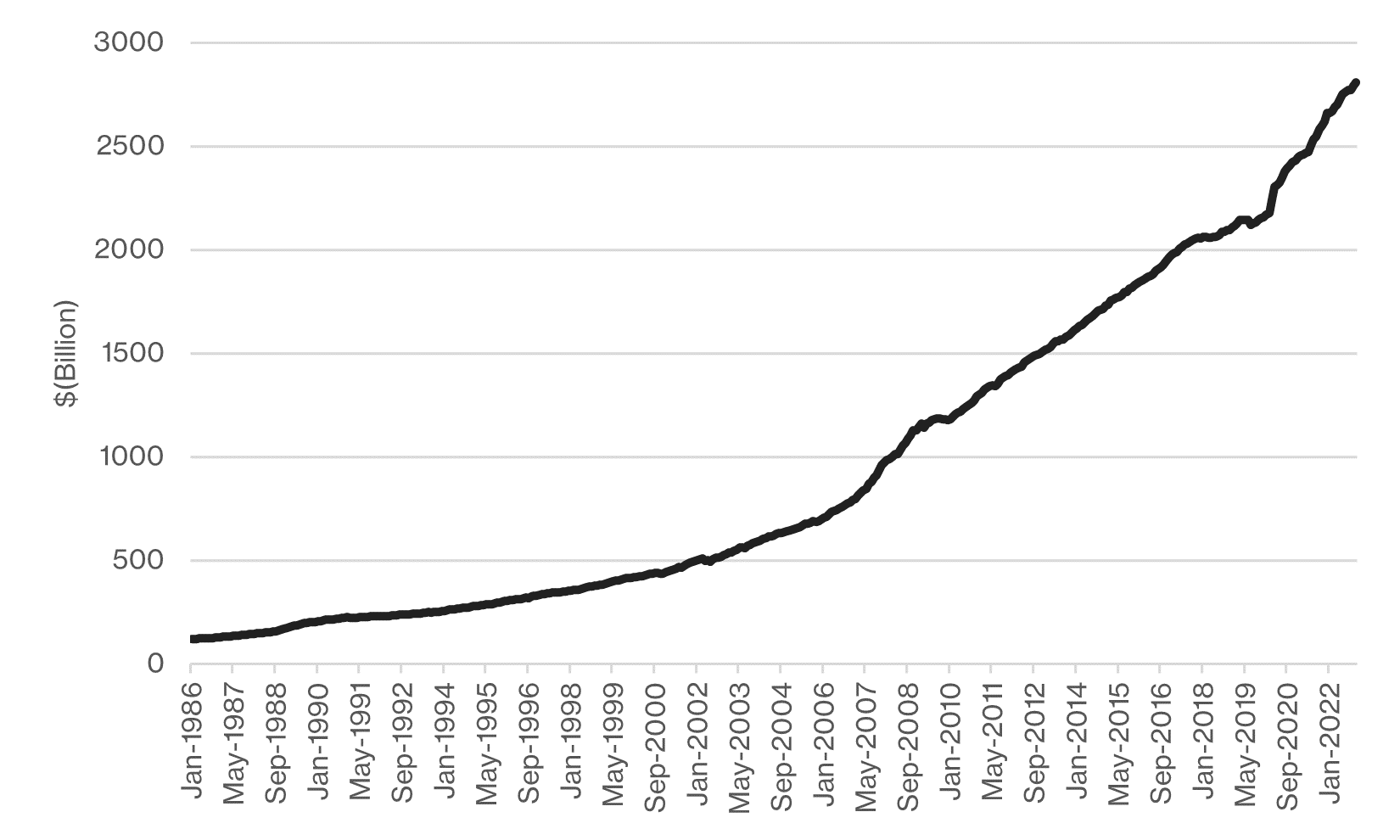

What was already an unstable monetary situation was exacerbated by the 2020 pandemic where an already-high money supply was expanded even further. Money supply had doubled during 2010s. In the first few months of 2020, it was expanded by another 11 percent. By the end of 2021, money supply had increased 23 percent from its December 2019 level. In the 10 years 2010 to 2019, money supply increased by $976 billion. Between January 2020 and December 2021, it was increased by another $500 billion. The money supply, measured by M3, is charted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Reserve Bank of Australia, M3 ($Billion)

Of course, most of this money spilled first into real estate, then into stocks and other assets (including crypto), and finally into goods and services.

Benefitting From Inflation

Not everyone is affected equally by inflation. Depending on what you buy or where or how you live, inflation might not bother you very much or it might completely ruin your household budget. Asset price appreciations accrue to those people with assets. While it’s not all “real” gains in wealth, holding assets that appreciate with inflation at least means that you’re not going backwards. And then there’s the illusion of wealth. People might think they have created real wealth for their families only to find that while their house might have doubled in value, the “real” gain is negligible once they consider what today’s money can buy relative to what they could buy with the amount they originally paid for their house.

If you use the RBA's inflation calculator (which, remember, reflects the “headline” rate only), you can see how much the real value of money has declined in the past twenty years. For example, let’s say that you bought a house for $400,000 in 2000. And let’s say that it was valued at $850,000 in 2022. More than doubled, right? Wrong. $400,000 in 2000 bought you the equivalent of $668,000 of goods in 2021 dollars. In real terms, your house has increased in value by 27%, not 112%. Big difference. And that’s if the headline inflation rate is fully reflective of changes in purchasing power… And it isn’t.

The Big Issue

Perhaps the biggest problem with money printing and inflation is that it messes up the information signals that guide business decision-making and capital allocation. Interest rates should be low when people are relatively patient and are saving a lot of (real) wealth. Interest rates should be high when people are relatively impatient and would rather spend than save (higher interest rates are needed to entice them to save). When interest rates are low, therefore, it signals to entrepreneurs and business decision-makers that (1) there is a pool of savings that can be used for longer-term ideas; and (2) people will not suddenly pull the rug out from under them, leaving projects unfunded and unfinished. If the central bank prints money, interest rates are artificially lowered. Entrepreneurs and decision-makers think there’s a pool of savings and a population of relatively patient savers waiting to grow their wealth through projects that take time, only to find that as soon as the printing press stops (as it must), the money disappears. Projects collapse. You can see this reflected most clearly in the string of collapsed building and construction companies in Australia.

The question turns to what can be done. Interest rate increases are accompanied by reductions in the growth of money supply. And money supply growth is slowing. In 2022, M3 in Australia grew by around 5 percent. Other solutions are less obvious.

Inflation means that there’s too much money chasing too few goods. One thing that can be done is to start working our way out of the problem by producing more. This is where labour productivity (output per worker or output per hour) is relevant.

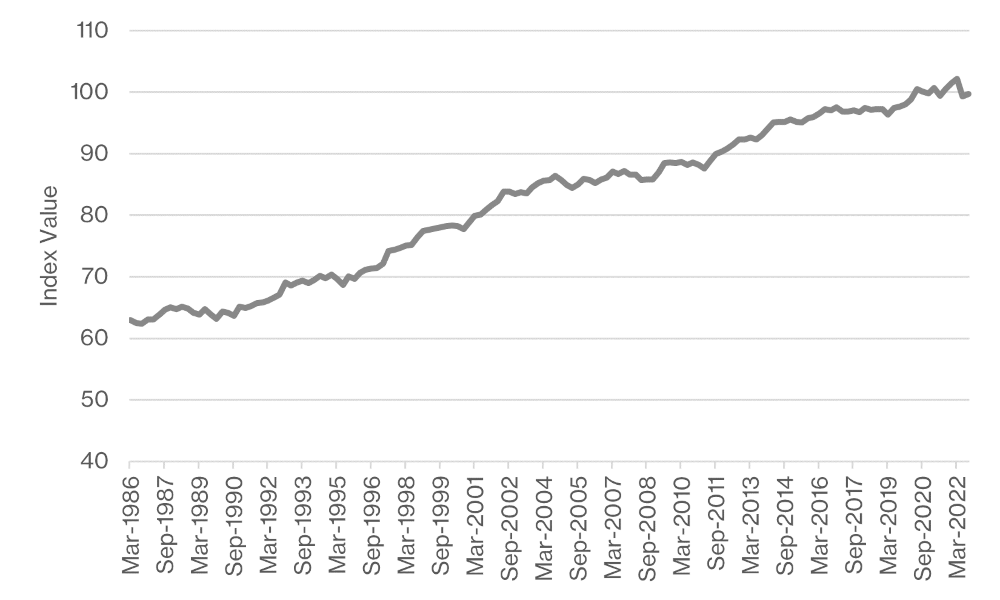

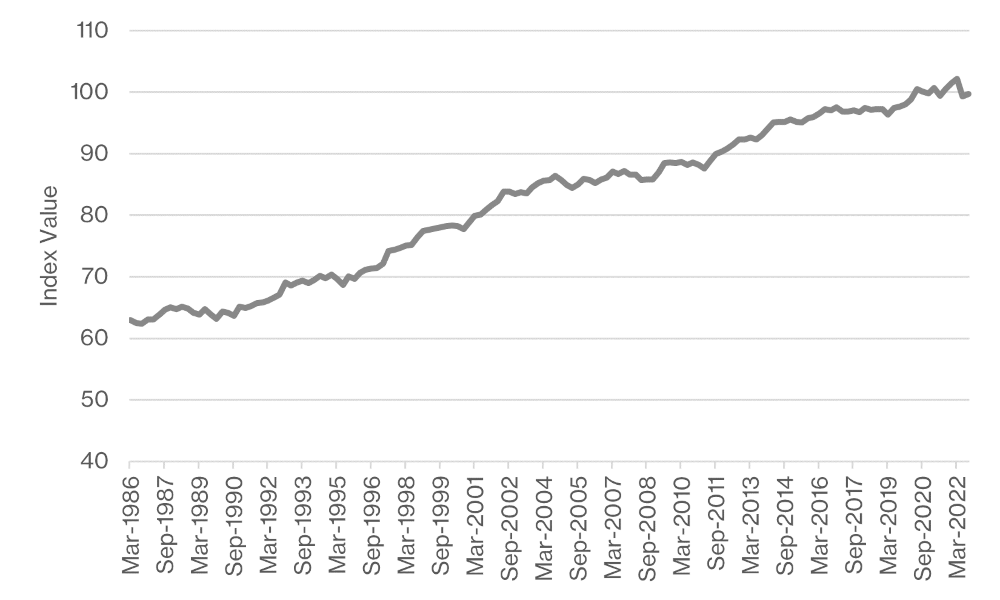

Figure 2: Reserve Bank of Australia, Non-Farm Labour Productivity per Hour

Unfortunately, labour productivity in Australia (and in most other Western economies) has been sluggish and it’s growing at a much, much slower rate than the money supply. Compare Figure 2 with Figure 1.

Labour productivity has not even doubled since 1986 while the money supply has increased by 2400%, from $119 billion to nearly $3 trillion, over the same period!

We were able to offset some of this slow productivity growth by importing cheaper goods from overseas, especially from China. When the supply chain was interrupted in 2020 and 2021, at precisely the time that there was even more money that needed soaking up, this pressure valve was no longer effective. An increase in labour productivity in Australia would go some way towards alleviating some of our problems. Another thing to consider is the regulatory framework and how it might impede business growth and output. If it’s hard to start a business and begin producing something, then that something might not get produced. And if it doesn’t get produced, it’s not going to soak up any of the money that’s floating around. Any business owner will tell you that they must comply with an array of regulations stemming from all levels of government.

Some regulations are essential. Others hold down production and productivity. Increasing interest rates is not the only thing that can be done to curtail inflation.

Discussion Question

How is the RBA’s inflation rate calculated? Do you think it reflects the true cost of living for the average person?

Further Reading

Monetary policy is discussed in Chapter 12 of Financial Institutions, Instruments and Markets, 9th edition

Read other posts

Why you should study Finance and Economics in the 21st Century

From Chicago to New York: Futures Trading and Microwave Popcorn

Basketball, Fund Managers, and the Hot Hand

The French Connection in Finance Theory

The Road to Cryptocurrency, Instalment # 1

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #2

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #3

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #4

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #5

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #6

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #7

Imagination and the Future of Cryptocurrency

Bigger Than FinTech: The Less Obvious Innovation Transforming Finance

NFTs: A Brave New World for Artists?

Sometimes, Inflatoin is the Only Way Out

I “Fink” Bitcoin Might Be a Good Idea After All

Bitcoin and Ethereum: Commodities or Securities?