One reason why economics is not the most popular choice among new university students is that apart from “economist” there are fewer obvious connections to jobs than in other areas of study where it is clear what you will “be”. Finance has the same problem but to a lesser degree. At least prospective finance students can aim to secure a job “in finance” or “financial services”. But both perceptions are problematic because they distract from the general applicability of the knowledge and the skills acquired by serious economics and finance graduates.

"Every course in economics and finance is a decision-making structure that can be used to make sense of and navigate through a complexity created by a humanity that will produce more than 463,000,000,000,000,000,000 (463 quintillion) bytes of information per day by 2025"

The case can be made that economics and finance are conduits for the acquisition of skills that are becoming increasingly prized. Analysis. Problem solving. Evaluation. But much more important even than this, is the value of economics and finance as a decision-making structure for an information intensive world. Every course in economics and finance is a decision-making structure that can be used to make sense of and navigate through a complexity created by a humanity that will produce more than 463,000,000,000,000,000,000 (463 quintillion) bytes of information per day by 2025. The economics and finance graduate is adept at managing information flow, a flow that has now become a raging torrent. Four examples can help us to illustrate this point.

1: Underlying Order & Gravitational Pull

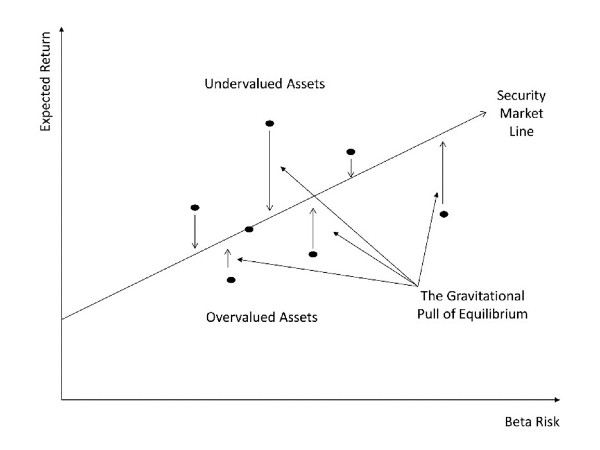

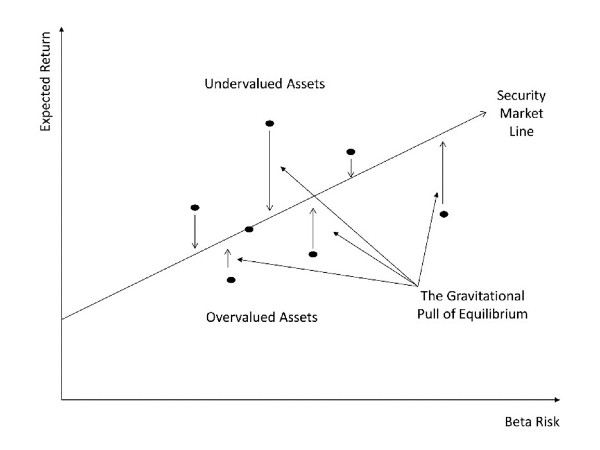

We explained in the previous post how in 1952 Markowitz was able to tap into the underlying structure of risk and reward to design an algorithm capable of identifying efficient portfolios (i.e. portfolios with the highest average return for a given level of risk). In the 1960s, financial economists were able to construct an asset pricing model, called the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), by building on the structure Markowitz had revealed. The idea is that every asset in the economy should have an expected return commensurate with its risk.

By spotting overvalued assets (with expected returns less than commensurate with their risk) and selling them short and spotting undervalued assets (with expected returns more than commensurate with their risk) and buying them, everything would be held in check by the combined trading activity of market participants. There would be a constant pull towards equilibrium. In a remarkable flash of intuition, they depicted this equilibrium scenario as a straight line, called the security market line (SML). Complexity becomes simplicity. The economics and finance graduate sees the underlying order (and understands the forces that disrupt it).

2: Corporate Finance

Nothing can be more intimidating than trying to picture the decision-making process that multi-national corporations apply to the choice of which new idea to pursue. Which new market should we enter? Which new product should we take to the market? Which firm should we acquire? Corporate finance theory is a simplifying structure for thinking about these types of decisions. Within this structure, the objective of corporate finance is to create shareholder value. The driver of shareholder value is free cash flow (what’s left for the owners from operating cash flow after allocating cash to working capital and long-term assets). The drivers of free cash flow are projects that return more than what they cost on a present value basis. That is, projects with a positive net present value (NPV). Projects with a positive NPV create shareholder value.

The picture that emerges is one where the corporate finance team ranks or orders each new idea according to its NPV. The highest ranked alternatives are selected (giving due consideration, of course, non-financial factors). Projects with a negative NPV are ignored. This reduces the problem to a prioritisation or ranking of alternatives by a single objective criterion. And if the picture is still not clear, ideas with positive NPVs are found above the SML. When people spot them and develop them, they begin to drift back towards the SML. This explains why corporations must constantly innovate. The returns generated by new ideas gradually erode over time due to the gravitational pull of equilibrium.

3: Macroeconomics

“Economics and finance are the information management powerhouses of the social sciences.”

The economic system is complex. Despite this, decisions must be made. Macroeconomics is that part of economic theory that deals with the whole economy, not individual economic behaviour. Macroeconomics is a decision-making structure. It depicts a relatively small collection of categories moving in concert with each other. Aggregate demand. The price level. Interest rates. Aggregate supply. Money supply. Government spending. National income. To visualise the economy as a multitude of individual decision-makers is a difficult task. To visualise a logical concert of a handful of categories or concepts is relatively straightforward. More than this, to a person trained in the logic of economics and financial economics, other decision problems can be similarly reduced to the essential categories and concepts. Information flows that may overwhelm others can be directed and organised more easily, pooling it for synthesis and dissemination. Economics and finance are the information management powerhouses of the social sciences.

4: Economics of Information: Algorithms & Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Our work is primarily concerned with decisions in contexts where even a marginal advance in our understanding of human behaviour can be vital (for example, disinformation and espionage). Decision theory, which is sometimes called the economics of information, depicts the decision-making problem as a prioritisation task. Although we have been living in an information age for a long time, developments are gathering pace. Or, at least they appear to be.

Without organising structures, the pace of change and the processing of information quickly becomes too much to handle. Overwhelmed decision-makers make bad decisions. Within firms, information structures exist to collect information and direct its flow through the organisation. These structures are fragile and can be broken, leaving the members of the organisation facing an unknown and rapidly changing world that appears more threatening and unstable because the very systems that should help to manage the information flow are disintegrating.

Take the prominent example of algorithms and AI. Information about these tools is flowing now in a torrent. Decision theory explains how information structures can be optimised to ensure that firms do not miss important information about these new developments. And, furthermore, information can be organised so that it does not appear to be overwhelming. Selecting new technologies is a ranking problem. Each new technology can be evaluated and ranked based on information collected in an orderly and structured way. The economics and finance graduate should be able to tell you how to accomplish this.

Discussion Question

What types of information are central to finance? How can the skills necessary to process this information be transferred to other contexts?

Further Reading

The textbook itself is an information structure that can be used to organise our thinking about a financial system constituted by financial institutions, instruments, and markets. Consider, for example, the loanable funds depiction of interest rate determination presented in Chapter 13. This helps us to visualise a complex piece of the puzzle.

Read other posts

Financial Literacy: The Road Out of Financial Anxiety

Supply and Demand: The Case of the Australian Dollar

The Sad and Sorry Tale of AMP Limited

People Are Afraid to Let Their Winners Run

Finding Warren Buffet & a Cool Head in a Crisis

Self-Managed Superannuation Funds: Cash Kings?

From Zero to $100 Billion in Sixty Seconds

Simple Maths, Long Term Damage

Are Share Prices Too Volatile?

If My Super Fund Performed Poorly, I’d Change… But I Don’t Remember It Performing Poorly

My Portfolio Might Be Up 10%, But that's A Loss!

Free Cash Flow: The Driver of Shareholder Value

Australia’s New Tech Index: A Local Version of the NASDAQ?

The Behavioural Economics of ‘Going on Tilt’

A Cup of Coffee and an Option Pricing Model

Yes Virginia, there is a Mortgage Tipping Point

How Universities Shape the Real World: The Case of Corporate Finance

Disinformation: Can is Sweep Investors off their Feet?

Hedge Funds, Satellites and Empty Carparks

The Battle for FinTech Supremacy: The Tech Titans Vs the Masters of the Universe

Algorithms in Finance? That's Nothing New

The Algorithm that finds the ‘Best’ Portfolio