Hedge Funds, Satellites and Empty Carparks

Published 27 November 2020

By Dr Peter J Phillips, Associate Professor (Finance & Banking) University of Southern Queensland

Hedge funds. These things are quite mysterious but, like all things finance and economics, the mystery goes away the more you learn.

In the United States, hedge funds are largely unregulated investment operations (managed funds), usually structured as partnerships with minimum buy-ins that exclude all but high-net-worth individuals. The regulations are lax because, presumably, high-net-worth individuals know what they’re doing with their money.

The hedge fund manager takes a percentage of the capital (win or lose) + a percentage of the investment returns as a fee. Whereas a traditional fund manager is mainly involved in traditional trades, picking companies and investing in them, a hedge fund manager uses a selection of more sophisticated strategies that open up additional opportunities.

For example, a hedge fund manager might use options to buy or sell the market’s overall volatility. Market volatility tends towards its historical average. When there is a spike in perceived riskiness, market volatility spikes and option prices rise (because they can be used to insure a portfolio against losses). A hedge fund manager might sell those options short, betting that volatility and perceived riskiness will subside and options prices fall. If this happens, the hedge fund will profit.

A simpler hedge fund trade that has become more common is called ‘long-short equity’. Based on sophisticated research and innovative data analysis, hedge fund managers look for companies that might be about to experience good news or bad news. They invest accordingly, going long if good news is expected and going short if bad news is expected.

"One thing I used to do in the old days was keep an eye on how full the carparks were at retailers that I might have wanted to invest in."

A hedge fund, as the name suggests, involves hedging the fund’s bets. As such, the fund manager might have reached a conclusion that a pharmaceutical company (let’s call it A) is on the verge of a breakthrough which will benefit the company and damage its rival (let’s call it B). The hedge fund goes long (buys) A to profit from the good news if and when it comes and short (sells) B to profit when the company suffers the fallout from its rival’s breakthrough. In the meantime, anything that generally impacts the pharmaceutical industry will not affect the hedge fund’s position. If the general news is bad, the hedge fund loses on A and gains on B. The hedge fund’s exposure is to the specific expected breakthrough for A. If that doesn’t come, the hedge fund may suffer a loss.

What sort of sophisticated research are we talking about? When it boils down to it, there’s only so much you can learn purely from the numbers. There is a statistical structure that connects all financial assets. If you can find them, inconsistencies can be exploited. But with strategies like long-short equity, bigger potential profits come from insights into companies’ real prospects.

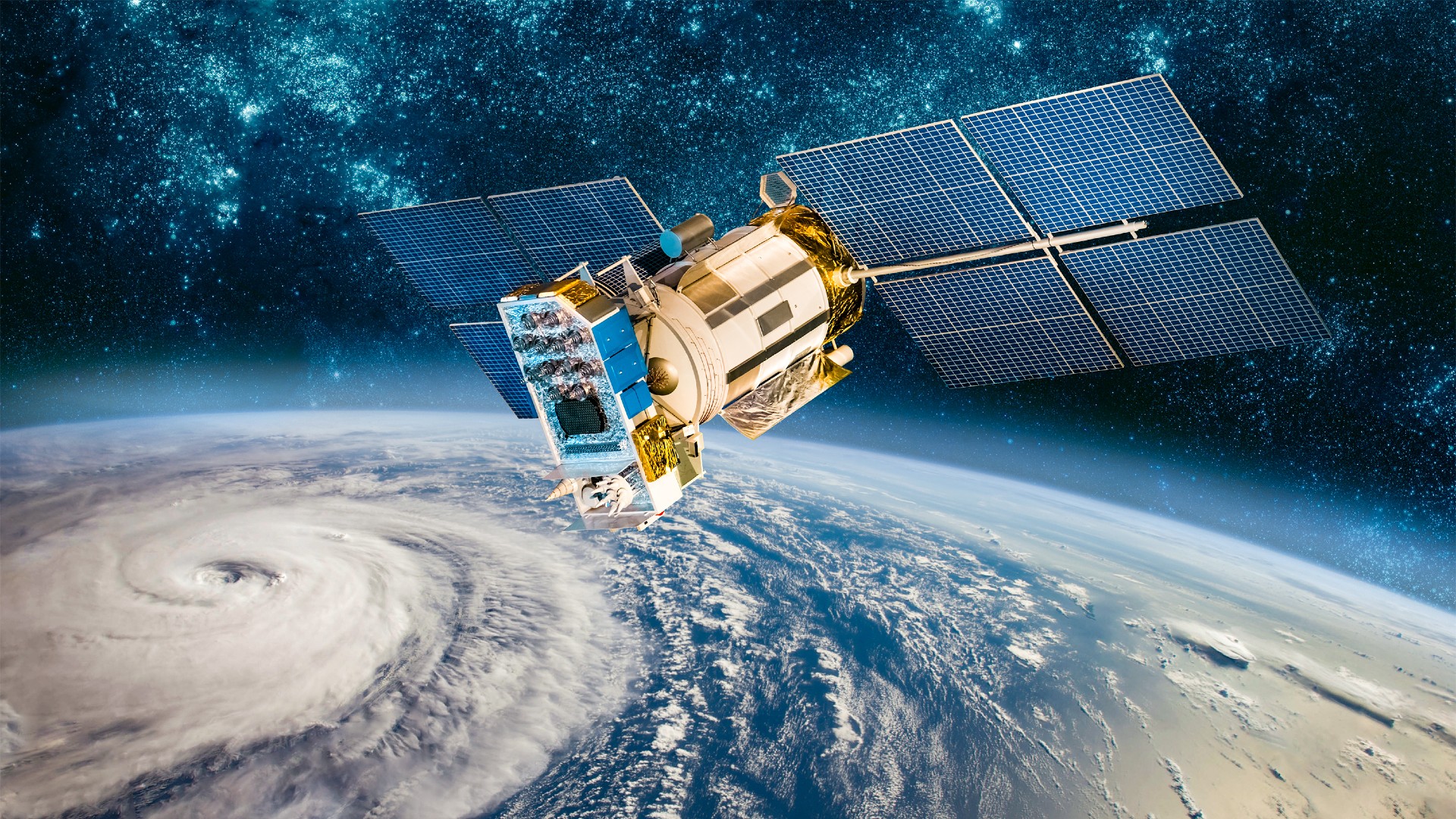

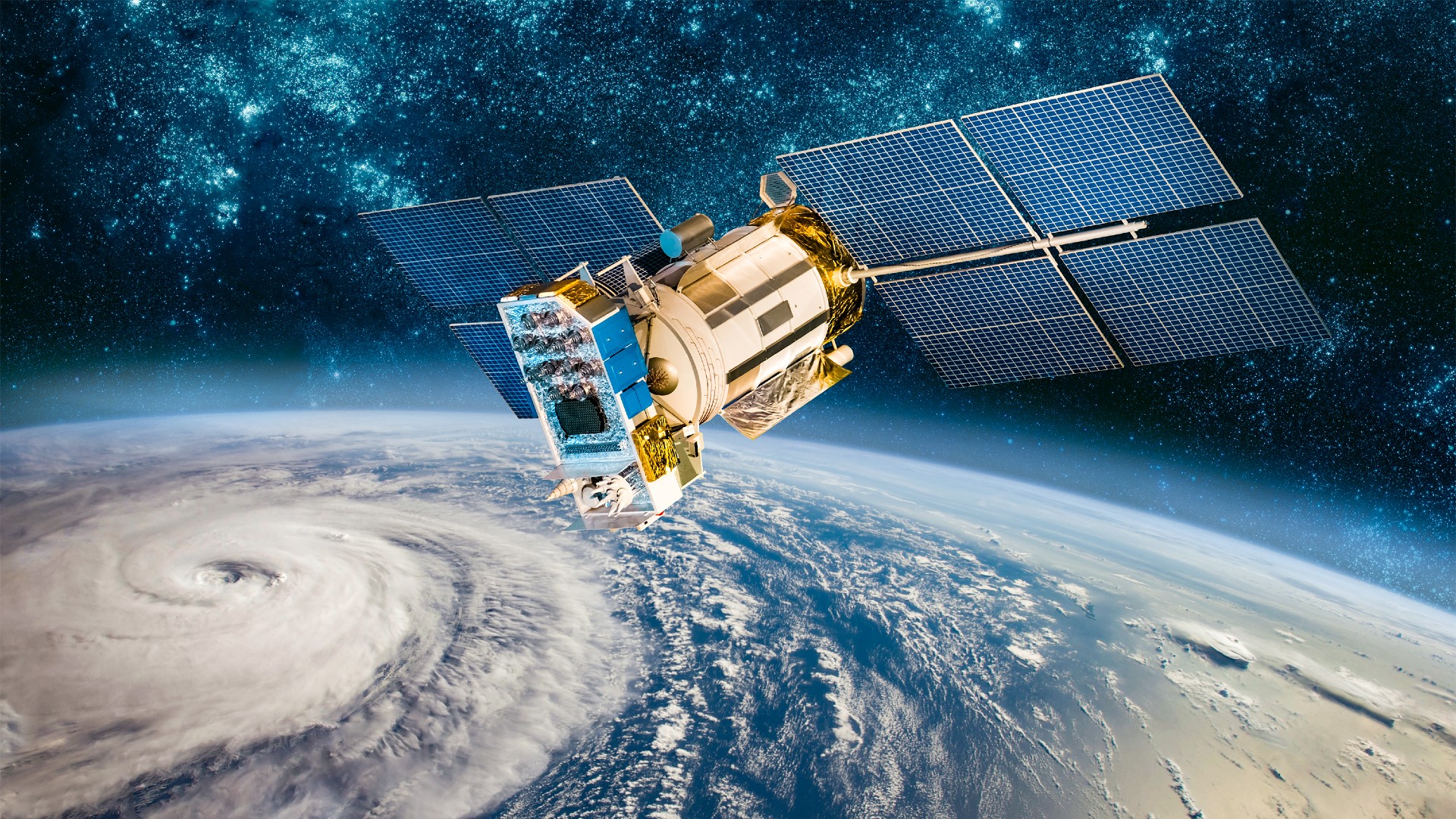

"Hedge funds are in the business of getting the ultimate bird’s eye view. By using satellites."

One thing I used to do in the old days was keep an eye on how full the carparks were at retailers that I might have wanted to invest in. Fund manager Peter Lynch used to watch the crowds at Dunkin’ Donuts. Or stake out particular product sections at major retailers to see how fast those products were selling. Can we do things like this on a grander scale? Yes, indeed. And hedge funds are in the business of getting the ultimate bird’s eye view. By using satellites.

In our post on space junk, we noted just how cheap it is now to launch material into space. In recent years, hedge funds have taken advantage of the new accessibility to space and have either acquired their own satellites or partnered with space companies. Just like I used to do in my little town, these satellites can be used to monitor car park traffic at retailers. Instead of one location, many can be monitored. For example, researchers showed that it is possible to develop a profitable trading strategy using this approach. As an indication of scale, the researchers monitored 67,000 sites, tracking nearly 5 million images for changes in car park traffic.

In addition to car parks, satellites can be used to gather insights into oil inventories. While some countries publish accurate and frequent reports of oil inventories, others are less clear. China, for instance. How could a hedge fund determine how China’s oil inventories are moving? They can use satellites to monitor activity at oil storage facilities and oil storage tank usage.

Yet another idea is to use satellite images of night-time lighting intensity to monitor a country’s general level of economic activity. Something to remember the next time you pull into a car park, drive past an oil refinery or switch on the lights for your back porch.

Discussion Question

Find out who two of the most prominent hedge fund managers are. What firms have they been associate with? Can you find details on their most famous trades?

Further Reading

Chapter 3 of the textbook presents our discussion of non-bank financial institutions. We address hedge funds briefly in section 3.8.

Read other posts

Financial Literacy: The Road Out of Financial Anxiety

Supply and Demand: The Case of the Australian Dollar

The Sad and Sorry Tale of AMP Limited

People Are Afraid to Let Their Winners Run

Finding Warren Buffet & a Cool Head in a Crisis

Self-Managed Superannuation Funds: Cash Kings?

From Zero to $100 Billion in Sixty Seconds

Simple Maths, Long Term Damage

Are Share Prices Too Volatile?

If My Super Fund Performed Poorly, I’d Change… But I Don’t Remember It Performing Poorly

My Portfolio Might Be Up 10%, But that's A Loss!

Free Cash Flow: The Driver of Shareholder Value

Australia’s New Tech Index: A Local Version of the NASDAQ?

The Behavioural Economics of ‘Going on Tilt’

A Cup of Coffee and an Option Pricing Model

Yes Virginia, there is a Mortgage Tipping Point

How Universities Shape the Real World: The Case of Corporate Finance