Decision Theory (or Information Economics): The Key?

Decision theory is the analysis of optimal decision-making under all contingencies. For example, a firm wants to develop the best pricing policy under all possible supply conditions (which are unknown or can only be described probabilistically at the time the policy is developed).

Game theory adds a strategic dimension. That is, the firm now considers the reaction of other firms in developing its pricing policy. The principles of decision theory (also called information economics or the economics of information) are sprinkled all over the social sciences. If we add its sister discipline, game theory, then the reach is even wider.

For example, international relations and criminology both have prominent rational choice research programs which draw on decision theory and game theory. While we might not be surprised to find information economics providing a part of the foundations for modern finance, everything makes a lot more sense when decision theory is spelled out in simple terms. At that point, everyone can see that there is a commonly used way of framing problems and analysing decisions and that an understanding of this “problem space” is useful to anyone studying any of the social sciences, not just economics or finance.

The name “rational choice” sweeps a lot of detail out of sight and does us very little good when trying to understand how problems are analysed. People imagine a perfectly cold and calculating decision-maker that never makes mistakes. This is not really the decision-maker depicted by decision theory. In fact, decision theory doesn’t really depict a decision-maker as such. What it does is develop a structure in which all problems are depicted in a certain way and within which everyone from a perfectly rational decision-maker to a bumbling buffoon can be studied as they try to select the best alternative.

Let’s describe this structure.

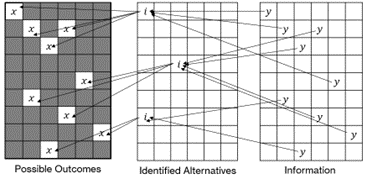

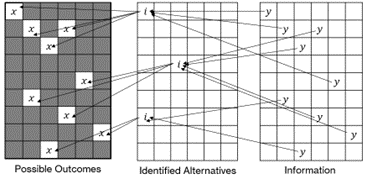

It boils down to alternatives (the things you can choose), the possible outcomes (what you might experience by making a choice), and the probabilities (what you think the chances are of experiencing an outcome). The problem is to identify the alternatives (call them the i’s), list the possible outcomes (let’s call them x’s), and associate each outcome with a probability (let’s call the probabilities p’s). The decision-maker “searches” or gathers information (call these signals y’s) until the problem space is complete. That is, until all possibilities have been identified. Of course, every decision-maker will place some boundaries around the problem space. If your decision involves buying a new refrigerator, you might restrict yourself to stores in your neighbourhood or brands you know or stores where your buy-now-pay-later company is accepted.

What does this look like? We like to draw this something like this.

The information that the decision-maker gathers is used to uncover alternatives and the outcomes that might be experienced if an alternative is selected. The information is also used to develop a set of (subjective) probabilities that are associated with outcomes. If there is risk but no uncertainty then, in theory, the decision-maker can completely fill in the problem space. Of course, the problem space might be delineated as we suggested above. As such, even a fully populated problem space is not a complete description of everything that could possibly happen. If the problem is subject to uncertainty, then the decision-maker cannot populate the problem space, even a strictly delineated one, no matter how much time is spent gathering information.

Rational choice is one type of decision-making process that can be applied to selecting the best alternative. A rational decision-maker will select the alternative that maximises expected utility. The expected utility for an alternative can be calculated by working out the utility of each outcome—this task is accomplished by running the x’s through a utility function such as ln(x) so that the x’s are transformed into u(x)’s—and multiplying each u(x) by the probability associated with that outcome. Summing across all outcomes gives the expected utility for the alternative. The alternative with the highest expected utility is the optimal choice given the information available.

Behavioural economics depicts a different type of decision-maker. This decision-maker is beset by several quirks of behaviour that can lead to a sub-optimal choice. Importantly, though, this decision-maker tries to solve the problem in the same way. That is, the structure of decision is the same. The idea of the problem space is the same. It’s just that this decision-maker makes systematic mistakes when evaluating the outcomes (x’s) and their probabilities (p’s). Behavioural economics also includes important boundaries on search and computation. People usually don’t gather information right up to the point at which its marginal benefit equals its marginal cost. They stop much sooner. And even though people might be able to compute the expected utility maximising alternative, they might not have the time or the computer-power to do it. Simply, if you’re busy or stressed, your computational ability is impaired even though you might be able to make better calculations if you had more time or more breathing space.

To me, the most interesting thing is that this process of delineating a problem space and searching for the best alternative seems to be almost universal both to human behaviour in general and to the formal work undertaken across the social sciences. And the initial delineation seems to depend on one’s background (culture, education, experience etc.).

My favourite example comes from finance. Realising the vast sea of information and possibilities that characterise the financial markets, in 1952 Harry Markowitz delineated the problem space along two measurable quantities: average (mean) returns and variance of returns (risk). Within this mean-variance space, optimal portfolios could be computed more easily and, in fact, Markowitz developed an algorithm to do so in 1956. While this appears strange, we can see that what he was really doing was capturing all the alternatives (individual stocks and portfolios) and the possible outcomes (x’s = returns) in a strictly delineated problem space. Together with the mean, the variance describes the probability distribution (the p’s) for the possible outcomes. Of course, he also captured the information (y’s) because the only information you need is the history of stock returns. Markowitz trapped the i’s, y’s, x’s, and p’s in a problem space that could be traversed by an algorithm to assist investors to identify the optimal portfolio.

His choices in delineating the problem space were not random, but cultural-sociological. He had been exposed to decision theory and operations research during his education and the early part of his career along with the optimisation techniques being experimented by pioneers in those fields. That he would delineate the financial markets problem space to enable the optimisation techniques to work is no surprise. This is not just an economist’s foible. There is an interesting research program in the field of “predictive policing”. The algorithms that underpin some of the main models are analogous to those that are used to study earthquakes and their aftershocks. And where did the developers of these predictive policing algorithms hang out? At UCLA, which is known for its research into earthquake predication.

Discussion Question

If decision-makers delineate a problem space, do the developers of algorithms and AI applied to finance problems do the same? Does this shape the outcomes of such applications?

Does this extend beyond finance to algorithms and AI in general? If so, what are the implications?

Read other posts:

The Velocity of Money and Central Bank Digital Currencies

Bitcoin and Ethereum: Commodities or Securities?

I “Fink” Bitcoin Might Be a Good Idea After All

Sometimes, Inflation is the Only Way Out

NFTs: A Brave New World for Artists?

Bigger Than FinTech: The Less Obvious Innovation Transforming Finance

Imagination and the Future of Cryptocurrency

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #7

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #6

The Road to Cryptocurrency Instalment #5