Simple Maths, Long Term Damage

Published 15 May 2020

By Dr Peter J Phillips, Associate Professor (Finance & Banking) University of Southern Queensland

As part of the government’s response to the Covid-19 (coronavirus) pandemic of 2020, people who fulfilled certain criteria were allowed to access a part of their superannuation ‘early’. This was not a completely new idea. Under normal circumstances, there is provision in the superannuation rules that permits people to access $10,000 when they face a period of financial hardship. Normally, relatively few people access this option. Perhaps relatively few even knew it existed.

According to the Australian Taxation Office, people affected by the pandemic could gain access to $10,000 of their superannuation before June 2020 and a further $10,000 between July and September 2020. To access these sums, people must meet the following criteria:

- You are unemployed.

- You are eligible to receive a job seeker payment, youth allowance for jobseekers, parenting payment (which includes the single and partnered payments), special benefit or farm household allowance.

- On or after 1 January 2020, either

- you were made redundant

- your working hours were reduced by 20% or more

- if you were a sole trader, your business was suspended or there was a reduction in your turnover of 20% or more.

Within a few weeks, more than 900,000 Australians had applied to access their superannuation early and at the height of the crisis the government estimated that around 1.7 million Australians would ultimately access the scheme (see ABC News). The impact that this will have on the future retirement incomes of these people is a concern that had to be weighed against the exigencies due to the pandemic.

While estimates of the future damage to Australia’s retirement income savings depend very much on the assumptions that we make, it is clear that only very basic financial mathematics is required to make the estimates. Let us try to get a best case scenario. Since 900,000 people definitely applied in the opening weeks of the scheme, the government’s estimate of 1.7 million does not look to be too high. Let us assume, therefore, that 1.7 million people withdraw some amount of their superannuation. Let’s further assume that they each withdraw just one lot of $10,000, not two lots. That would give us a total withdrawal of $17,000,000,000 (i.e. $17 billion).

The next two assumptions are really the most critical. First, what rate of return could be expected to be earned on the funds if they remained in the superannuation system? Something like the long-term average share market return would be plausible with a little bit taken off to allow for the fact that superannuation portfolios are rarely 100 percent allocated to shares but have a selection of safer, lower return, assets. Let us settle then on a relatively conservative and plausible 6 percent p.a.

The second assumption concerns the length of time that the funds would have remained in the superannuation system. If everyone who accessed the scheme was 80 years old, then the withdrawals would not have been invested for the very long term. If everyone who accessed the scheme was 20 years old, then the withdrawals would have potentially been invested for another 45 years, maybe longer. Anyone who knows anything about compound interest knows that the time period of the investment is a critical factor in determining the amount to which an investment can grow.

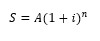

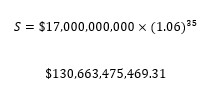

Let us assume that the average age is 30. And assume that the withdrawn funds would have been invested until age 65. That is, for a further 35 years. How much, then, would $17,000,000,000 have grown to if it had not been withdrawn? We only need formula 8.6 to figure it out:

Where S is the amount to which the investment grows (future value), A is the amount invested, i is the rate of return and n is the number of periods (in this case years):

That’s $130 billion that Australians won’t have 35 years from now, provided the assumptions hold good. If you don’t agree with one or more of the assumptions, it’s very easy to change them and compute the number again. You will find, however, that even the very lowest plausible estimates (bordering on implausibly low) still yield a very large future value amount. Any way we look at the problem, the damage to Australia’s future retirement income savings is substantial.

Can we say anything positive? All problems are multidimensional. It is possible that the pandemic changes ways of doing business and, indeed, the structure of the economy in ways that turn out to be positive. In the midst of a crisis, most people are focused simply getting through it. As the clouds clear, it might be possible to glimpse an upside that might offset, to some degree, the downside that we have been discussing.

Discussion Question

Do you agree with the assumptions that form the basis for the calculation? What happens if you change the rate of return? The average age (and therefore the length of time)?

Further Reading

Financial mathematics is not everyone’s cup of tea but as we can see, some basic knowledge can go a long way in shedding light on important policy issues. The basics of financial mathematics are presented in Chapter 8 of Financial Institutions, Instruments and Markets 9e.

Read other posts

Financial Literacy: The Road Out of Financial Anxiety

Supply and Demand: The Case of the Australian Dollar

The Sad and Sorry Tale of AMP Limited

People Are Afraid to Let Their Winners Run

Finding Warren Buffet & a Cool Head in a Crisis

Self-Managed Superannuation Funds: Cash Kings?

From Zero to $100 Billion in Sixty Seconds