The Behavioural Economics of ‘Going on Tilt’

Published 13 August 2020

By Dr Peter J Phillips, Associate Professor (Finance & Banking) University of Southern Queensland

There’s a Matt Damon and Edward Norton film from 1998 about two card players. It’s called Rounders. Towards the beginning of the film, Matt’s character makes an interesting comment that has stuck in my mind ever since I saw it. He says that a player can go on tilt and lose all of his money. For many years, I have been meaning to return to this idea and see if it’s possible to explain how the investment decision-making process might be disrupted when the investor ‘goes on tilt’.

Going on tilt, it turns out, might have originally referred to when a pinball player becomes so frustrated that he lifts the machine up a little bit—tilts it—to stop the ball going down the gap between the two paddles and ending the game. Matt’s character in the movie was referring to a situation where a card player finds himself chasing unlikely outcomes in the hope of recovering an unexpected loss. The result is undisciplined play and, potentially, total losses. What happens when an investor goes on tilt? And how can this be avoided?

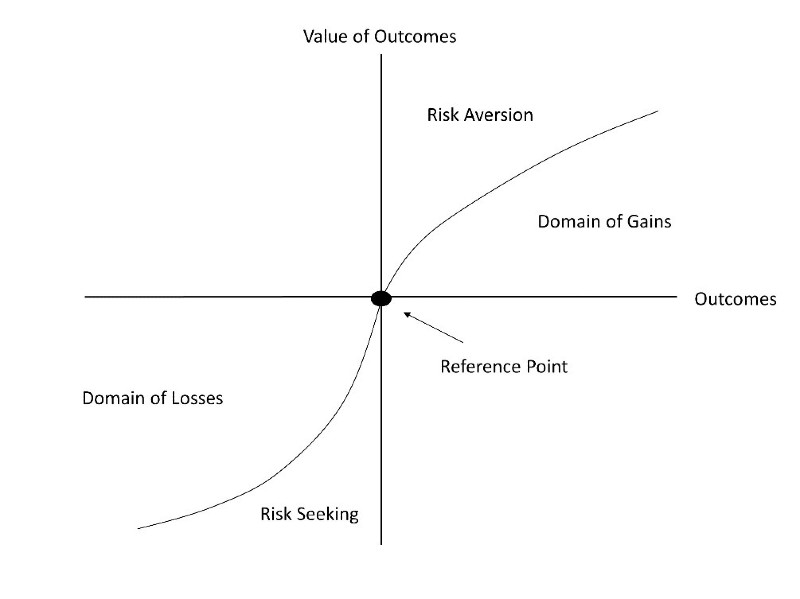

To me, Kahneman & Tversky’s (1979) prospect theory provides the answer. We mentioned Kahneman & Tversky in a previous post. Prospect theory is a model of the decision-making process. It includes a number of ‘quirks’ that Kahneman & Tversky uncovered in a series of psychology experiments. The theory is the foundation for behavioural economics and finance. One of its most famous features is the S-shaped value function. This depicts the way in which the investor (or any person facing risk) assigns values to alternative outcomes. In the centre is the reference point. This might be a goal (e.g. I’d like to earn 5 percent from this investment) or it might be an outcome achieved by a friend (e.g. my friend earned 10 percent and I would like to earn more). Depending on whether an outcome is above or below the reference point, the investor values it in a different way.

In the domain of gains, the investor is risk averse and approaches the evaluation of outcomes with caution. Economists depict this by a concave function. In the domain of losses, the investor is risk seeking. Economists depict this by a convex function. The two functions ‘inflect’ at the reference point forming an S-shaped function unique to prospect theory. The theory tells us that an investor may be compelled to bear considerable risks in an attempt to recover from a loss. This can lead the investor to throw good money after bad and might result in big losses. I think that this is one step towards going on tilt. But there is more to it.

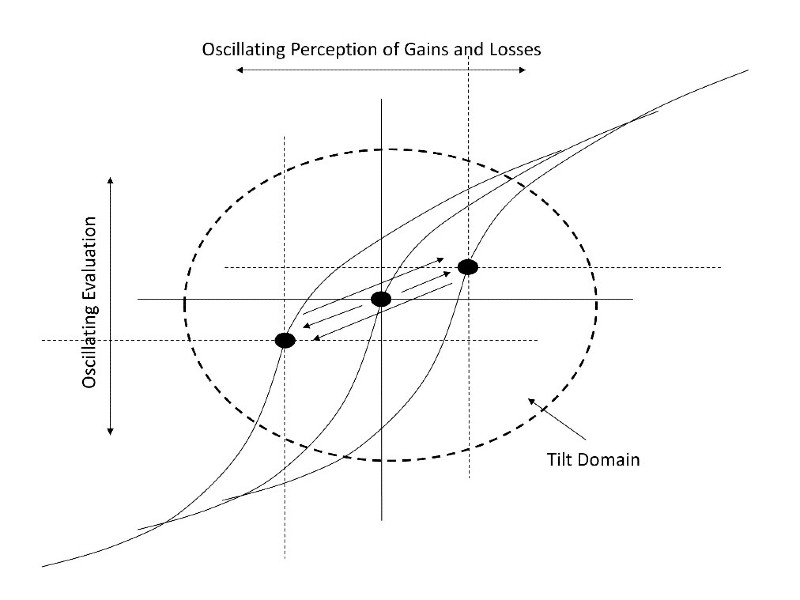

Going on tilt is even more destructive than risk seeking in the domain of losses. It’s not only characterised by more risk seeking but by a general confusion and frustration. I would depict this as not only finding oneself in the domain of losses but as a situation in which the reference point itself breaks loose from its moorings and begins to float freely. When this happens, there’s no way to evaluate outcomes definitively as gains or losses because what might be perceived as a gain one moment is perceived a loss the next. In the ‘tilt domain’, investors perceive the potential outcomes as gains, then losses, then gains and valuation oscillates accordingly. When the investment decision is made, it is based on pure emotion rather than any real judgement or evaluation of the potential outcomes. It will only be a matter of luck if things turn out well. It might look like this:

This can happen to any investor who finds himself in the domain of losses without a stable point of reference. To avoid this unpleasant state of affairs, the investor needs careful, long-term investment planning that includes a clear investment goal. A portfolio must be designed to grow wealth over time and the ups and downs that the market experiences must be accommodated within the portfolio structure. The investor cannot rush for the exits at the first sign of trouble only to rush back into the market once the trouble abates. There’s always trouble of some sort or other! If you cannot afford to lose a certain amount of money, do not put that money at risk. Rather, start with a smaller amount, save diligently and patiently accumulate wealth over time. As we also explained in an earlier post, modest sums can grow very large given enough time. If you think of your long term investment goal as your stable reference point and you keep it firmly in the forefront of your mind, you lessen the chance that you will one day find yourself chasing losses and, even worse, going on tilt.

Discussion Question

Explain how having a long term investment objective as a reference point might help to avoid taking unnecessary and counter-productive investment risks.

Further Reading

In Chapter 7 of the textbook we discuss behavioural finance. It is in this very interesting part of finance theory that we find some important insights into the ways in which investors behave and, of course, the keys to correcting those behaviours (as much as possible).

Read other posts

Financial Literacy: The Road Out of Financial Anxiety

Supply and Demand: The Case of the Australian Dollar

The Sad and Sorry Tale of AMP Limited

People Are Afraid to Let Their Winners Run

Finding Warren Buffet & a Cool Head in a Crisis

Self-Managed Superannuation Funds: Cash Kings?

From Zero to $100 Billion in Sixty Seconds

Simple Maths, Long Term Damage

Are Share Prices Too Volatile?

If My Super Fund Performed Poorly, I’d Change… But I Don’t Remember It Performing Poorly

My Portfolio Might Be Up 10%, But that's A Loss!

Free Cash Flow: The Driver of Shareholder Value

Australia’s New Tech Index: A Local Version of the NASDAQ?