When We Talk About Inflation, We Quote the CPI, But We Forget the PPI

Over the past several years, with inflation an issue for the first time in a long time, a new generation of people have been introduced to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which is the measure of inflation that is most widely used and reported on. The CPI is important because it’s the rate that the Reserve Bank says it wants to keep within the target range of 2-3%. If the CPI gets above 3%, the odds of an interest rate increase go up. If the CPI is in the range, or below it, there’s a greater chance that interest rates will be cut. During 2021 and 2022, the CPI was well above and outside the target range, prompting the RBA to raise interest rates. For this reason, it’s a good idea to learn more about what the CPI is, its strengths and weaknesses, and to keep an eye on what’s happening to it.

As we have mentioned in previous posts, if the inflation rate is positive, prices are rising. We must be careful not to confuse a falling inflation rate with falling prices. Only when the inflation rate turns negative, will prices fall. Like most people, you would have noticed a big increase in the price of groceries over the past few years. Once a week, I buy a similar basket of goods. My rough estimate is that the price of this basket of goods has increased by at least 25 percent since 2021. Hang on! At no stage has the inflation rate been 25%! No, but the accumulated price increase of a series of smaller, positive inflation rates over the period adds up. In fact, even if we concede that the CPI is not a perfect measure of inflation and certainly not a perfect measure for everyone, using the CPI to compute what has happened to the price of a $100 basket of goods in late 2020, we find that the basket will cost at least $120 today. While inflation measured by the CPI is now 2.8% p.a. down from 7.8% p.a. in late 2022, prices are still going up. I need a series of negative inflation reports to get the price of my basket down from $120, back to $100.

The CPI reports inflation from the consumer’s perspective. While imperfect, it will reflect the average person’s experience at the shops. But when we’re down at the shops and things are getting more expensive each month, it’s natural to think that it must be something the shops are doing. After all, it’s their prices that we’re paying.

Only when we read, for instance, that bird flu has produced an egg shortage, or a cyclone has reduced the banana harvest, do we attach a deeper story to the prices in the store.

We forget that the supermarkets purchase the goods from a multitude of other companies and operations, themselves purchasing inputs from many others. Probably the only thing that really breaks through into the news is the occasional story about how much the supermarkets pay farmers and whether the prices they pay are fair. That’s something that’s obviously very difficult to get to the bottom of. But it’s not only farmers. Supermarkets must pay the companies that produce the breakfast cereal, the chips, the coffee, the tea, the toothpaste, the tissues, the vitamins, the pasta, the canned soup… And each one of these producers must pay a multitude of other people. Truck drivers, growers, energy companies, machinery manufacturers, chemical companies, fertiliser companies, refrigeration companies… By the time a product ends up in the supermarket, the price the consumer pays must be split a lot of different ways among a lot of different people.

If we see inflation for the consumer is going up, as measured by the CPI, is there a way to see whether the people who are making the products are experiencing rising prices or is it purely something being experienced at the consumer’s end? Yes, it’s called the Producer Price Index (PPI).

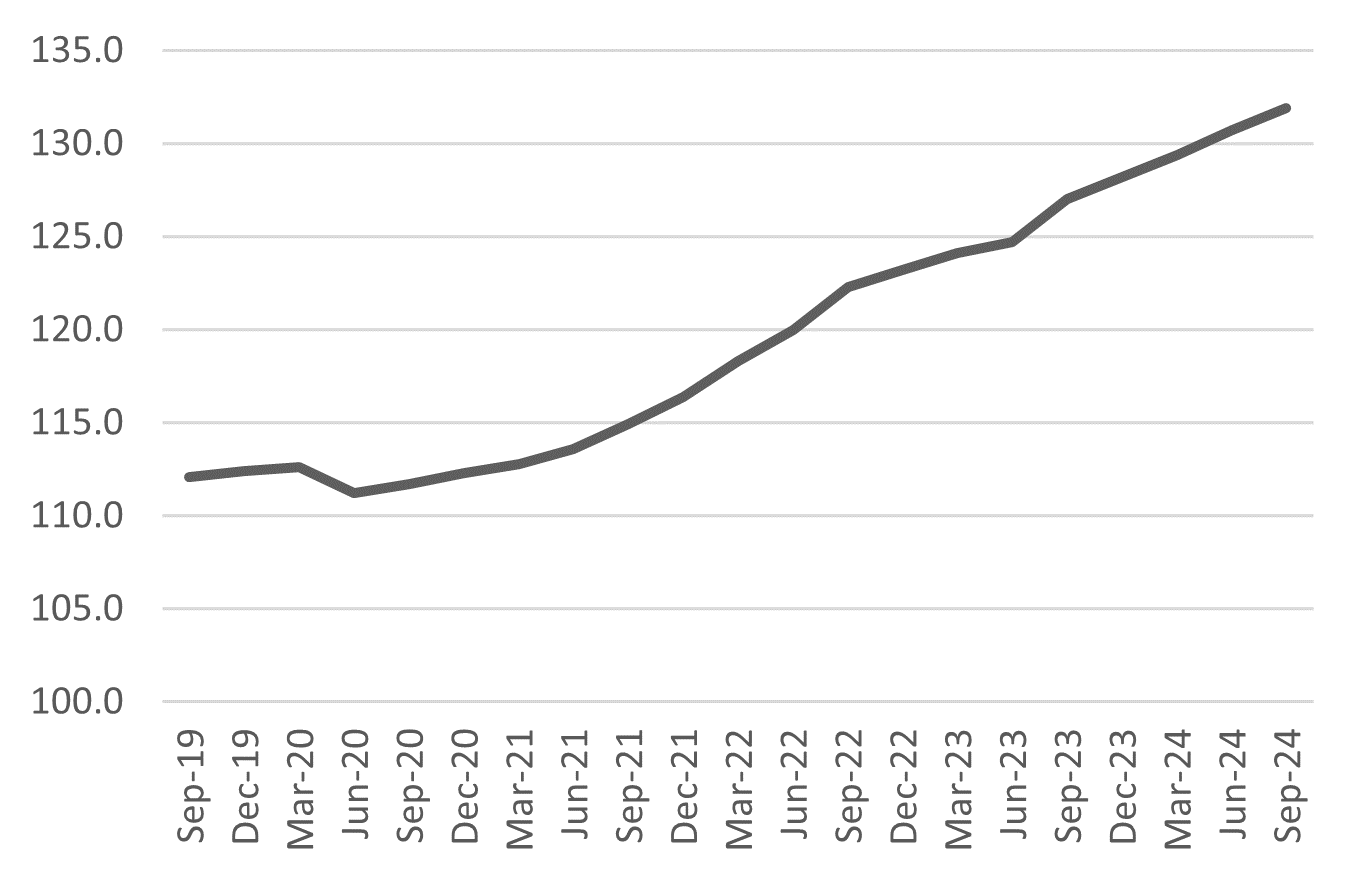

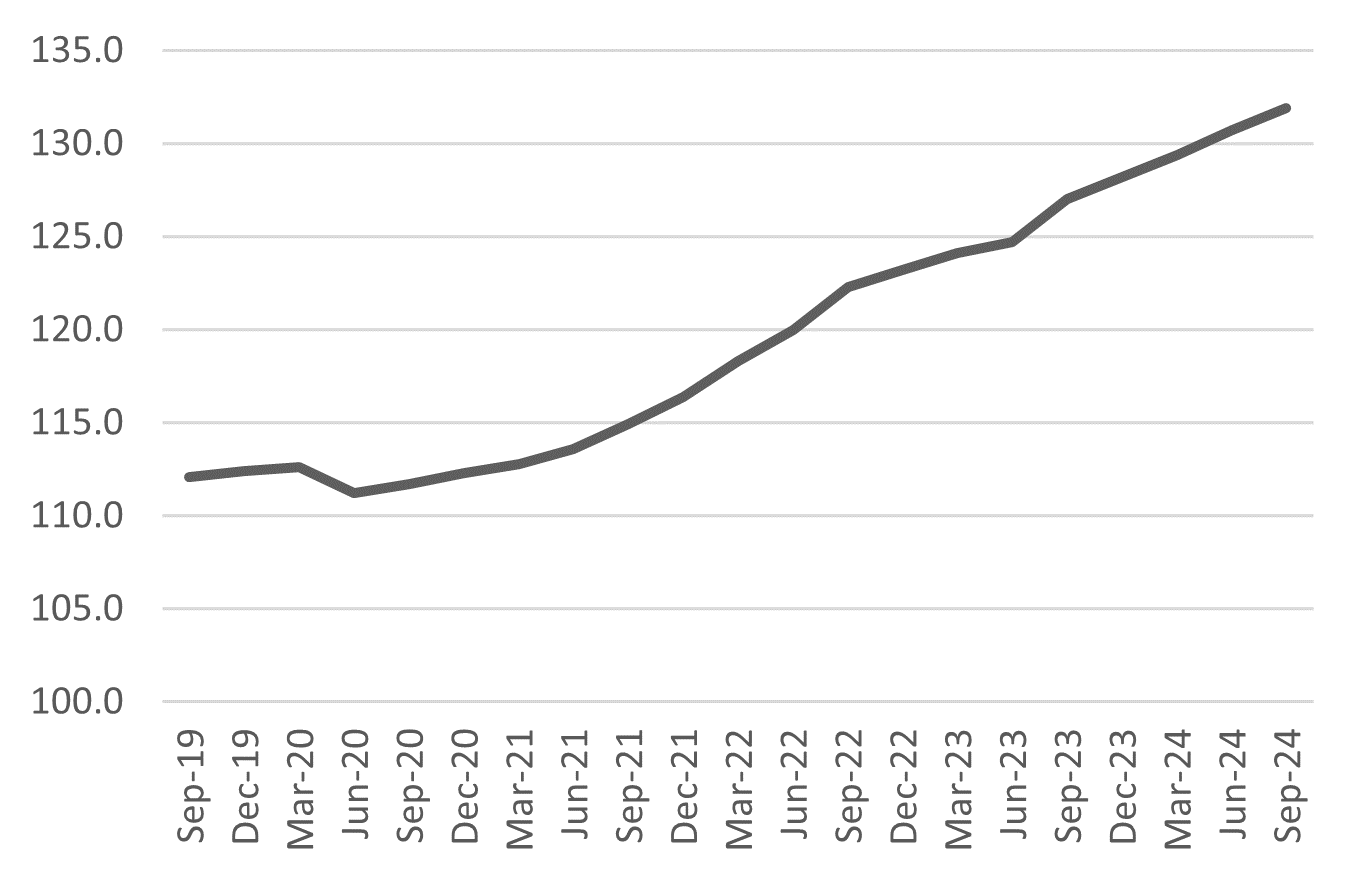

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, “The Australian PPIs measure the price change of products (goods and services) as they leave the place of production or as they enter the production process. This price change is measured from the perspective of the industries that produce goods and services. Whereas other measures, such as the Consumer Price Index (CPI), measure price change from the consumers' perspective.” Great. So, what’s the PPI been doing? Here’s the story:

The cost of producing in Australia has risen sharply since 2020. The PPI, like the CPI, won’t capture the experience of every producer. In general, though, we can say that what would have cost about $100 to produce before the pandemic, now costs around $120. That’s about the same as the consumer’s experience.

The reasons for these increased costs depend on what industry we consider. Increased rents were a big contributor across the board. Energy prices fell in recent months, taking some pressure off, but prices have been higher and going up in recent years. Transport was more expensive because of trouble in the Red Sea. Companies that employ technical professionals found they had to pay more because of labour shortages in some areas. Some healthcare costs increased because it’s more expensive to run a small surgery/practice (e.g., electricity). And there’s also short-term financing costs. Many firms borrow for 60 or 90 days to keep their operations running. The cost of this type of finance has risen with the increase in interest rates.

Overall, we can see that things have become more expensive since 2020 and this is not just a thing that happens at the end of the supply chain. Higher prices are affecting the whole supply chain, from start to finish. Some companies will fare better than others at passing the increased costs along to the consumer, though that only keeps their profits steady, it doesn’t add to their profits. Others will try methods like reducing the amount of product in each packet to keep the price the same (i.e., shrinkflation), thinking that consumers will only pay a certain amount and no more for their product. Less obviously, some will use cheaper inputs such as vegetable oil instead of butter. Others will simply not survive. Recognising that inflation is not only something that we experience down at the shops but is a wider and deeper problem tells us that we need a deeper understanding of where the inflation came from in the first place.

Discussion Question

Some businesses have resorted to reducing the amount of product (number of chips, number of biscuits etc) to keep the sticker price the same for consumers. Most people think this is a sneaky move but if producer prices are going up, the alternative would be to raise the price or take a loss (margins in a lot of these businesses are quite thin). Would companies be better off just letting the prices reflect increased production costs rather than reducing the amount of product and keeping the price the same?